Portraiture in American art dates back to the time of the colonies. From the late eighteenth century onward, beginning with the work of such artists as John Singleton Copley, Gilbert Stuart, and Charles Peale, issues surrounding representations of race, class, and gender have inevitably crept into the milieu of figurative painting, primarily when American society has reached critical junctures in its political history. Painting—although the medium is periodically proclaimed to be dead by critics—has been the site of several groundbreaking movements that have sought to deconstruct and disrupt the laden narrative of American art by formally pushing the bounds of the medium while also questioning the all-too-easy tendency to view it as an apolitical form of representation. Today, figurative painting has been met with renewed interest, particularly through artists who acknowledge its problematic development and seek to confront this long course head on.

Amir H. Fallah is a Los Angeles-based artist who is currently exploring portraiture (and still-lifes) with many of these issues in mind. In the process of composing his portraits, he engages his subjects by first visiting their homes and photographing them with their possessions. Returning to his studio, he works from these photographs and primarily focuses on the forms and concepts of inanimate objects and how they might be brought together to signify the presence of his subjects, who are rendered anonymous in the most unconventional way.

Below is an interview conducted with the artist in June via email as he prepared for an exhibition of still-lifes at The Third Line gallery`s Project Space in Dubai. Amir explains his process and reveals some of the inspirations for this striking new body of work.

Maymanah Farhat (MF): Your latest series of painting can be divided between two distinct bodies of work: floral still-lifes indebted to the Old Master traditions of Dutch and Flemish painting and a more playful grouping of portraits in which your subjects remain semi-anonymous. How did these separate yet somehow related projects come about?

[Amir H. Fallah, "Unknown Portal" (2012). Image copyright the artist. Courtesy of The Third Line gallery and Gallery Wendi Norris.]

[Amir H. Fallah, "Unknown Portal" (2012). Image copyright the artist. Courtesy of The Third Line gallery and Gallery Wendi Norris.]

Amir H. Fallah (AHF): The two bodies of work are actually very similar. Still life and portraiture are two of the most popular modes of art making. It’s a challenge to take these two tropes of art and try to breathe new life into them.

With the portraits all the superficial signifiers such as age, race, gender, and class are stripped away and you are left to decode their identity through the objects they surround themselves with. In the floral still lives I am reimagining paintings from the Dutch/Flemish Golden Age and remixing them with new imagery and techniques. Often times the reference painting is scanned and collaged back into the new painting. Color and composition change but the essence of the original source material is embedded in the new work. Also by using a wide array of material from collage and airbrush to oil paint I complicate the painting process, which adds a visual tension to the works. In both bodies of work I’m interested in taking preexisting stories, images, histories, and memories and deconstructing and remixing them.

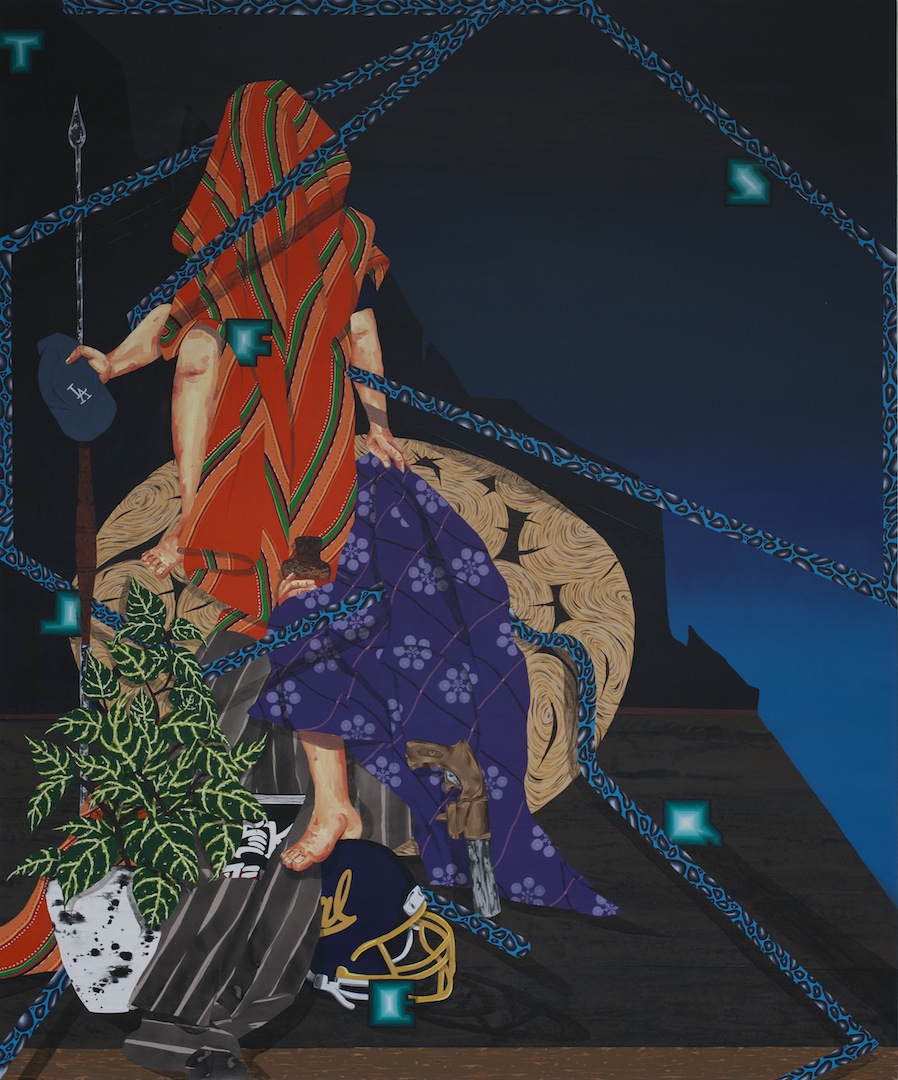

[Amir H. Fallah, "The Earth is But One Country (Eastern Bred, Southern Fed) (2013). Image copyright the artist. Courtesy of The Third Line gallery and Gallery Wendi Norris.]

[Amir H. Fallah, "The Earth is But One Country (Eastern Bred, Southern Fed) (2013). Image copyright the artist. Courtesy of The Third Line gallery and Gallery Wendi Norris.]

MF: In both, you appear to be exploring the formal and conceptual ends of “arrangement,” which corresponds to your forthcoming exhibition "The Arrangement" at Project Space. And yet the compositional concept of stacked, juxtaposed, and visually built forms has been prevalent in your work for some time, here I am thinking of your earlier fort/tree-house paintings from 2006. Do you begin with such arrangements in mind or do they somehow take shape in the process of painting?

AHF: I always think of my paintings as stacks or piles of imagery. Everything is visually and conceptually piled on top of one another. At the beginning this happened naturally but over time it became more methodical and planned. Formally, I’m interested in how this stacking creates a painting that is simultaneously flat and spatial depending on where one looks at the work. I’m also interested in the idea of stacking content. In the portraits a person’s identity emerges through juxtapositions of inanimate objects. It’s similar to walking into a stranger’s home and trying to sort out who they are by looking at the furnishings that they live with. Their home starts the story but your imagination is left to finish it.

MF: What are the intended spatial effects of such forms, which have a psychedelic/otherworldly feel to them in that natural, celestial, and corporeal elements come together within spaces that are denoted with architectural motifs (i.e. structures, platforms, or pedestals that are painted with the semblance of wood, marble, or metal materials)?

AHF: I think of the spaces in my work as a mental or psychological space. There is a reference to a physical space but it is very generic and basic. Even the background colors are not specific. The backgrounds are usually a color gradation going from dark to light. It’s not clear if it’s day or night, cold or warm, indoors or outdoors. This vagueness allows the viewer to forget about the surroundings and focus on the objects and figures that they are confronted with. As for the platforms or pedestals that the figures stand on I think of them as open stages. There are minimal pieces of furniture there for the figure to interact with but the main event is the objects at the center.

MF: What I find interesting is that, in a way, you regularly return to the concept of portraiture despite a heavy emphasis on objects and space. The fort/tree-house paintings were based on interview questionnaires that you provide to friends. With their responses to questions such as “What are your first memories of building a fort or tree house?” came paintings of makeshift structures in deserted landscapes and installations of childhood forts constructed from the everyday details of domestic settings. In the same sense that one could say such works are a type of portraiture—one based not on direct figuration of your subjects but rather on subjective experiences—your new series of portraits maintains a degree of anonymity while also sustaining the personal dimensions of those who act as your models. Do you view such work as a type of portraiture and if so how has the process of interacting so intimately with your subjects impacted your work?

AHF: Yes you’re quite right. I viewed all of these bodies of works as portraits. When I was in college I made several series of self-portraits and dealt with my personal experiences. Later on I did an entire body of work that was primarily abstract but the works were titled after my failed relationships. For me it’s important to take the practice of art making (specifically painting) and connect it to my reality.

I find it impossible to make art about subjects and people that I don’t interact with in some form. I envy those that can make work that doesn’t relate to them but for me I have to be involved with my subjects and content emotionally on some level or I feel as if I’m creating an illustration instead of making art. As I make all of my work I allow my personal experiences, memories, and likes/dislikes to mix into the work. My worldview and outlook is mixed right into the portraits, which creates a layer of honesty on my end but also skews the sitter’s reality.

MF: Although the process of entering the homes of your subjects and selecting objects that will be placed alongside them in their portraits is somewhat invasive (evincing a degree of voyeurism), you immediately negate this aspect by covering your subjects and releasing their image from the scrutinizing eye of the viewer. What inspired this new take on portraiture and how might it relate to or depart from the long history of portraiture in general, which dates back to ancient times? When embarking on this new series, were you thinking and working with such historical trajectories in mind?

[Amir H. Fallah, "Warrior of the Golden State" (2012). Image copyright the artist. Courtesy of The Third Line gallery and Gallery Wendi Norris.]

[Amir H. Fallah, "Warrior of the Golden State" (2012). Image copyright the artist. Courtesy of The Third Line gallery and Gallery Wendi Norris.]

AHF: Initially I wanted to find a way of depicting the figure while painting as little of the body as possible. I wanted to boil things down to their essence and deconstruct our idea of the body. Over time I realized that by covering the identity of the figure I was removing all the visual signifiers that we use to construct someone’s identity. I also began to paint the flesh in unnatural hues and hide any features that may allude to gender. What we are left with is the reference of a figure and not much more which forces the viewer to start paying attention to the juxtaposition of the fabrics, trinkets, and objects that the figure is surrounded by. These items, the debris of life, receive a new prominence in the painting and help the viewer put together the identity of the sitter.

The covering of the figure was also influenced by the practice of women wearing the hijab in the Muslim world. I grew up with family members who where devout Muslims and wore hijabs. I’m interested in how identities can be disguised, manipulated, protected, and exposed through concealment of the body. It creates a barrier of privacy, which allows the viewer to forget the superficial and focus on what the individual says and what their actions are. For me this is a very intriguing concept that I wanted to explore both for women and men. How do you describe someone when the superficial identifiers are veiled?

MF: Although perhaps conceptually unrelated, when first coming across these new portraits, I immediately thought of Islamic miniature painting and the images of saints and prophets in which their faces are covered with cloths in order to honor the precept of not rendering the likeness of holy figures. In compositional design and the regal posture of your subjects—and most certainly in your use of different patterns—I am reminded of Qajar portraits and earlier examples of Persian painting. Yet at the same time, I read somewhere that the poses are, in fact, from historical examples of Western portraiture. Are these multivariate references intentional? To what extent do such seemingly disparate visual cultures tie into your practice?

[Amir H. Fallah,"The Laws of Order" (2012). Image copyright the artist. Courtesy of The Third Line gallery and Gallery Wendi Norris]

[Amir H. Fallah,"The Laws of Order" (2012). Image copyright the artist. Courtesy of The Third Line gallery and Gallery Wendi Norris]

AHF: I actually look at Persian miniature painting quite a bit. I have several books on the subject and there are many references to it in my work. The borders, the visual stacking (flat perspective), and the dense patterning and ornamentation have all been heavily influenced by growing up around and looking at miniature paintings.

You are correct that the poses are taken from western works but I think in a way the merging of all these references is an accurate portrait of me, an artist who was born in Iran, lived in Turkey and Italy and finally settled down in the US. It’s only natural for me to view the world as one giant pool to draw inspiration from and work into my paintings and sculpture.

MF: I also read that your artistic origins are in graffiti. Is this true or did street art and a studio-based practice evolve at the same time?

AHF: Yes this is true. I became interested in graffiti as a young teenager. There was an excitement and freedom to it that grabbed my attention. As I became more involved with graffiti I started to look at art to improve my graffiti and eventually I decided to focus my time on fine art. Although I don’t make paintings about graffiti there are many subtle references to that world in my work like my interest in colors and ornamentation. I also love the challenge of working on a large scale, which I think is clearly a result of painting graffiti for many years; once you’ve covered an entire building in graffiti making a big painting is easy.

MF: Naturally your background in so many subcategories of visual culture leads to me to ask about Beautiful/Decay, the art magazine that you founded in 1996 and currently publish from Los Angeles. How did B/D begin and how has it evolved from those beginnings? Given that it covers such a wide range of art and visual culture, has it influenced your artistic approach or worldview—or is it the other way around, meaning that your own interests served as a springboard for the magazine?

AHF: Beautiful/Decay has always been an extension of my studio practice to a certain extent. I initially started it as a way of documenting and sharing artists, designers, and creatives that influenced my work. As the brand grew so did the project’s ambition but it’s always informed my studio practice whether directly or indirectly.